Altijd handig om te weten wat je nou eet, aangezien sommige fabrikanten er soms net een cryptisch geschreven geheel van maken. Doe er je voordeel mee.

Educate and dominate

WHAT ADVERTISERS DON'T WANT YOU TO KNOW

Looking for healthy, natural foods to bolster your gym gains? Here's how to separate the reality from the sales pitch when it comes to 8 common food labels.

by Matthew Kadey, MS, RD Jul 16, 2014

You're making your way through the grocery aisles, and you're faced with a number of choices. The all-natural baked chips or the multi-grain ones? Free-range eggs or the much cheaper regular orbs?

Well, you're not alone. These days, food packages are increasingly littered with label claims designed to pull at your health strings and get you to take the bait. It's hard to make heads or tails of it all, and to some extent, food makers count on that confusion.

A survey conducted by the Consumer Reports National Research Center found that many consumers are willing to shell out more of their hard-earned cash for certain label claims like "all natural" and "hormone free." Yet most grocery shoppers have misconceptions when it comes to what these cryptic and vague slogans actually entail. Here are some of the most common labelling tricks that could be costing you money, or worse, blowing up your physique.

If you believe this food label means you're getting a straight-from-the-dirt product, think again. The marketing around "all-natural" is so egregious that it's now plastered on a number of packaged foods with a laundry list of ingredients far removed from Mother Nature such as corn syrup, white flour, and so-called "natural flavoring."

The United States FDA has not imposed an official definition of "natural" other than the product should not include anything artificial or synthetic. The USDA, which regulates meat and poultry, says that a product can be "natural" if it "contains no artificial ingredient or added color and is only minimally processed (a process that does not fundamentally alter the raw product)."

"THE UNITED STATES FDA HAS NOT IMPOSED AN OFFICIAL DEFINITION OF "NATURAL" OTHER THAN THE PRODUCT SHOULD NOT INCLUDE ANYTHING ARTIFICIAL OR SYNTHETIC."

"THE UNITED STATES FDA HAS NOT IMPOSED AN OFFICIAL DEFINITION OF "NATURAL" OTHER THAN THE PRODUCT SHOULD NOT INCLUDE ANYTHING ARTIFICIAL OR SYNTHETIC."

This loosey-goosey definition, however, doesn't make any guarantees about how the animals were raised or whether the animals were given antibiotics or hormones. In short, "natural" is not synonymous with "healthful."

Fight Back: Ignore the natural sales pitch and choose your foods based on the nutrition facts panel and ingredient list. The latter should be as short as possible rather than reading like a chemistry quiz. Remember, it doesn't get any more all-natural than whole fruits, vegetables, nuts, and whole-grains. Foods labelled "organic" are still your best guarantee against genetically modified foods and meats or dairy laced with hormones and antibiotics.

WHEN THE LABEL SAYS: "NO HIGH-FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP"

For many health-savvy consumers, high-fructose corn syrup is similar to cyanide—something to avoid at all costs. That's because studies suggest that high intakes can spiral into fat gain and diseases like type 2 diabetes. Avoiding it isn't easy, either, because it's pumped into everything from bread to ketchup. Food manufactures take advantage of this collective corn syrup paranoia by bolstering the idea that their product is free of this dreaded sweetener. Yet, the item could very well be chock-full of other sugar euphemisms like evaporated cane juice, agave, and brown rice syrup—all of which have a similar effect on your waistline.

Fight Back: When buying packaged foods, again pay the most attention to the ingredient list, where several sweeteners lurk. One trick: Any ingredient ending in -ose is almost certainly sugar. You can also look for the "no sugar added" or "unsweetened" labels for a better chance of avoiding the sweetener beatdown.

WHEN THE LABEL SAYS: "WHOLE GRAIN"

For the sake of your fitness gains and overall health, it's always a good idea to seek out whole grains and their nutrient-rich profiles over refined grains. But be careful not to be lured automatically by items like breads and crackers touting their whole-grain dominance. Harvard researchers recently discovered that foods labelled as "whole grain," such as those carrying the industry-sponsored yellow Whole Grain stamp, were more likely to be higher in sugar and calories, as well as having a heftier price tag, than their whole-grain counterparts without the label.

Fight Back: To avoid falling into another sugar trap, when shopping for grain products you should always check the Nutrition Facts panel for options with the least amount of sugar, while also peeking at the ingredient list for the presence of sweeteners like glucose—one of the most common -ose words. The higher up an ingredient is on the list, the more it is found in the food.

Harvard scientists recommended looking for carb-based products with a 10-to-1 ratio of carbohydrates to fiber. So if an item has 40 grams of carbohydrate, ideally it should also contain at least 4 grams of fiber. Breads products with this ratio or lower were found to have more fat-fighting fiber and less sugar than foods with a higher ratio. A "high fiber" label means there's at least 5 grams of fiber present in each serving of the product.

WHEN THE LABEL SAYS: "MULTI GRAIN"

And just when you thought bagging a healthy loaf of bread couldn't be any more challenging. Bread products with the slogan "multi-grain" or "made with whole grain" are often white bread in disguise. That's because the first ingredient listed is often wheat flour, which is just refined white flour in disguise. It just happens that whole grains are found somewhere in the ingredient list, but often not in a leading role. In fact, the FDA has never said that any of the multi-grains have to actually be whole grains.

Fight Back: For any packaged grain-based product such as breads, cereals and crackers, the first ingredient listed should be a whole grain. That means you want to look for the word "whole" or "brown" as in whole wheat, whole rye or brown rice flour. But don't stop there. If a sugar follows soon after, look for a less sweet alternative. Also keep an eye out for the "100% whole grain" claim. This is actually regulated by the FDA and means that all grains used in the food are indeed whole.

WHEN THE LABEL SAYS: "REDUCED FAT"

During the '80s and '90s, when dietary fat was being demonized by the mainstream media, many food manufactures came out with versions of their products (peanut butter, salad dressing, etc.) that were touted as being "lower in fat" or "fat reduced." These types of items still populate store shelves. After all, what could be better than being able to slather peanut butter on your morning toast with less fatty baggage?

Well, here's the kicker. To make up for the flavor lost when fat is stripped away from nut butter, salad dressing, or yogurt, companies often pump in sugar . The added sugars mean the calorie count between the "reduced fat" and "regular" items is often negligible. Trading the heart-healthy monounsaturated fats found naturally in peanut butter for highly refined sugar is actually a step backward, health-wise.

Fight Back: Don't fear the fat. We all need some in our diets for optimal health and fitness gains. Just to cite one example, you're much better off selecting a plain Greek yogurt with 2 percent fat than you are a sugar-laden flavored version with no fat.

WHEN THE LABEL SAYS: "DARK CHOCOLATE"

A raft of research has found that the antioxidants in dark chocolate can do everything from supporting heart health to improving muscle efficiency during exercise. That's why it's become the acceptable cheat food for gym rats—and why an increasing number of food companies use the term "dark chocolate" to add nutritional allure to their cookies and energy bars.

Only, here's the catch: Not all dark chocolate is created equal. In an ideal world, dark chocolate would be a guarantee that you get more antioxidant-rich cocoa than sugar. However, if you take a look at the ingredient list of some products claiming to be made with dark chocolate, you'll notice that after the chocolate listing in the ingredient list is a bracket containing the ingredients that are used to make the so-called "dark chocolate."

And guess what? More often than not, it seems like sugar is the leading ingredient, meaning that the dark chocolate isn't such a dark delight after all. The problem lies in the fact that there is no official classification for what percentage of cocoa a dark chocolate has to contain, and food manufactures seem more than happy to exploit this.

Fight Back: Whether you select a straight-up dark chocolate bar or a packaged food which claims to contain dark chocolate, be sure that chocolate liquor or cocoa mass, which is where the antioxidants can be found, is listed in the ingredient list before sugar. Ideally, you want a bar that says its cocoa content is at least 60 percent.

WHEN THE LABEL SAYS: "FREE RANGE"

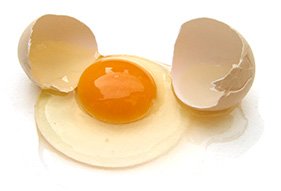

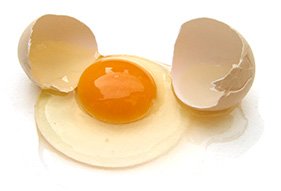

Packed with top-notch protein and a host of other essential nutrients, eggs are a near-perfect food for fitness fanatics. And even better if you can source free-range eggs; research shows they are even more awash in nutrients. Case in point: A 2014 study in the journal "Nutrition" discovered hens which were provided outdoor access made eggs with significantly higher vitamin D levels than the eggs produced by birds which were confined to the indoors. Exposure to sunlight is believed to be the reason why the hens were able to drop eggs that were richer in vitamin D.

But unscrambling egg labels can be tricky: "Free-range" eggs are supposed to come from hens allowed outdoor access while "free-run" means the birds are allowed to move freely in an indoor facility free of cages but likely don't spend anytime basking in sunshine. Unfortunately, neither label is tightly regulated. For example, the ease of outdoor access and the amount of time so-called "free-range" chickens actually spend in the sunshine is poorly regulated. And the range can mean anything from a large grassy field to a narrow pathway between barns to only a small concrete slab attached to a barn. What's more, there also isn't any mandate about how much time birds which produce "certified organic" eggs must spend in the great outdoors.

Fight Back: To be certain your white orbs come from birds that regularly see the light of day, it's best to befriend a local egg producer who raises smaller flocks and query them about their egg-producing methods. One tip off of a true free-range egg is a yolk that has an orange hue, which comes from the carotenoid antioxidants present in their foraged food.

WHEN THE LABEL SAYS: "REDUCED SODIUM"

Excessive salt intake may spike blood-pressure numbers, and some people find that it encourages water retention, leading to a physique that looks puffy, not chiselled. Logically, then, many fitness folks seek lower-sodium versions of their favorite foods.

"IF YOU'RE CONCERNED ABOUT YOUR SODIUM INTAKE, LOOK FOR THE LABEL "LOW SODIUM" ON ITEMS LIKE SOY SAUCE, FROZEN PIZZA, SOUPS, AND BREADS."

There's a big difference between "low sodium" and "reduced sodium," however. The latter simply means that it contains 25% less sodium than the original. If the original product such as chicken broth contained 900 milligrams of sodium per serving, the "reduced-sodium" version could still contain a lofty 675 milligrams of salt. Similarly, "light in sodium" entails the item only harbors 50 percent less sodium than its higher-salt counterpart.

Fight Back: If you're concerned about your sodium intake, look for the label "low sodium" on items like soy sauce, frozen pizza, soups, and breads. This is a guarantee that the product contains 140 milligrams of sodium or less per serving. "No salt added" means just that, no salt was added in the processing of the product. The nutrition facts panel may still show a certain amount of sodium, but this comes from sodium naturally present in the foods—such as tomatoes—used to make the product

http://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/what-advertisers-dont-want-you-to-know-about-food-labels.html?mcid=facenutrition03071714

Educate and dominate

WHAT ADVERTISERS DON'T WANT YOU TO KNOW

Looking for healthy, natural foods to bolster your gym gains? Here's how to separate the reality from the sales pitch when it comes to 8 common food labels.

by Matthew Kadey, MS, RD Jul 16, 2014

You're making your way through the grocery aisles, and you're faced with a number of choices. The all-natural baked chips or the multi-grain ones? Free-range eggs or the much cheaper regular orbs?

Well, you're not alone. These days, food packages are increasingly littered with label claims designed to pull at your health strings and get you to take the bait. It's hard to make heads or tails of it all, and to some extent, food makers count on that confusion.

A survey conducted by the Consumer Reports National Research Center found that many consumers are willing to shell out more of their hard-earned cash for certain label claims like "all natural" and "hormone free." Yet most grocery shoppers have misconceptions when it comes to what these cryptic and vague slogans actually entail. Here are some of the most common labelling tricks that could be costing you money, or worse, blowing up your physique.

1

WHEN THE LABEL SAYS: "NATURAL"If you believe this food label means you're getting a straight-from-the-dirt product, think again. The marketing around "all-natural" is so egregious that it's now plastered on a number of packaged foods with a laundry list of ingredients far removed from Mother Nature such as corn syrup, white flour, and so-called "natural flavoring."

The United States FDA has not imposed an official definition of "natural" other than the product should not include anything artificial or synthetic. The USDA, which regulates meat and poultry, says that a product can be "natural" if it "contains no artificial ingredient or added color and is only minimally processed (a process that does not fundamentally alter the raw product)."

"THE UNITED STATES FDA HAS NOT IMPOSED AN OFFICIAL DEFINITION OF "NATURAL" OTHER THAN THE PRODUCT SHOULD NOT INCLUDE ANYTHING ARTIFICIAL OR SYNTHETIC."

"THE UNITED STATES FDA HAS NOT IMPOSED AN OFFICIAL DEFINITION OF "NATURAL" OTHER THAN THE PRODUCT SHOULD NOT INCLUDE ANYTHING ARTIFICIAL OR SYNTHETIC."This loosey-goosey definition, however, doesn't make any guarantees about how the animals were raised or whether the animals were given antibiotics or hormones. In short, "natural" is not synonymous with "healthful."

Fight Back: Ignore the natural sales pitch and choose your foods based on the nutrition facts panel and ingredient list. The latter should be as short as possible rather than reading like a chemistry quiz. Remember, it doesn't get any more all-natural than whole fruits, vegetables, nuts, and whole-grains. Foods labelled "organic" are still your best guarantee against genetically modified foods and meats or dairy laced with hormones and antibiotics.

For many health-savvy consumers, high-fructose corn syrup is similar to cyanide—something to avoid at all costs. That's because studies suggest that high intakes can spiral into fat gain and diseases like type 2 diabetes. Avoiding it isn't easy, either, because it's pumped into everything from bread to ketchup. Food manufactures take advantage of this collective corn syrup paranoia by bolstering the idea that their product is free of this dreaded sweetener. Yet, the item could very well be chock-full of other sugar euphemisms like evaporated cane juice, agave, and brown rice syrup—all of which have a similar effect on your waistline.

Fight Back: When buying packaged foods, again pay the most attention to the ingredient list, where several sweeteners lurk. One trick: Any ingredient ending in -ose is almost certainly sugar. You can also look for the "no sugar added" or "unsweetened" labels for a better chance of avoiding the sweetener beatdown.

For the sake of your fitness gains and overall health, it's always a good idea to seek out whole grains and their nutrient-rich profiles over refined grains. But be careful not to be lured automatically by items like breads and crackers touting their whole-grain dominance. Harvard researchers recently discovered that foods labelled as "whole grain," such as those carrying the industry-sponsored yellow Whole Grain stamp, were more likely to be higher in sugar and calories, as well as having a heftier price tag, than their whole-grain counterparts without the label.

Fight Back: To avoid falling into another sugar trap, when shopping for grain products you should always check the Nutrition Facts panel for options with the least amount of sugar, while also peeking at the ingredient list for the presence of sweeteners like glucose—one of the most common -ose words. The higher up an ingredient is on the list, the more it is found in the food.

Harvard scientists recommended looking for carb-based products with a 10-to-1 ratio of carbohydrates to fiber. So if an item has 40 grams of carbohydrate, ideally it should also contain at least 4 grams of fiber. Breads products with this ratio or lower were found to have more fat-fighting fiber and less sugar than foods with a higher ratio. A "high fiber" label means there's at least 5 grams of fiber present in each serving of the product.

And just when you thought bagging a healthy loaf of bread couldn't be any more challenging. Bread products with the slogan "multi-grain" or "made with whole grain" are often white bread in disguise. That's because the first ingredient listed is often wheat flour, which is just refined white flour in disguise. It just happens that whole grains are found somewhere in the ingredient list, but often not in a leading role. In fact, the FDA has never said that any of the multi-grains have to actually be whole grains.

Fight Back: For any packaged grain-based product such as breads, cereals and crackers, the first ingredient listed should be a whole grain. That means you want to look for the word "whole" or "brown" as in whole wheat, whole rye or brown rice flour. But don't stop there. If a sugar follows soon after, look for a less sweet alternative. Also keep an eye out for the "100% whole grain" claim. This is actually regulated by the FDA and means that all grains used in the food are indeed whole.

During the '80s and '90s, when dietary fat was being demonized by the mainstream media, many food manufactures came out with versions of their products (peanut butter, salad dressing, etc.) that were touted as being "lower in fat" or "fat reduced." These types of items still populate store shelves. After all, what could be better than being able to slather peanut butter on your morning toast with less fatty baggage?

Well, here's the kicker. To make up for the flavor lost when fat is stripped away from nut butter, salad dressing, or yogurt, companies often pump in sugar . The added sugars mean the calorie count between the "reduced fat" and "regular" items is often negligible. Trading the heart-healthy monounsaturated fats found naturally in peanut butter for highly refined sugar is actually a step backward, health-wise.

Fight Back: Don't fear the fat. We all need some in our diets for optimal health and fitness gains. Just to cite one example, you're much better off selecting a plain Greek yogurt with 2 percent fat than you are a sugar-laden flavored version with no fat.

A raft of research has found that the antioxidants in dark chocolate can do everything from supporting heart health to improving muscle efficiency during exercise. That's why it's become the acceptable cheat food for gym rats—and why an increasing number of food companies use the term "dark chocolate" to add nutritional allure to their cookies and energy bars.

Only, here's the catch: Not all dark chocolate is created equal. In an ideal world, dark chocolate would be a guarantee that you get more antioxidant-rich cocoa than sugar. However, if you take a look at the ingredient list of some products claiming to be made with dark chocolate, you'll notice that after the chocolate listing in the ingredient list is a bracket containing the ingredients that are used to make the so-called "dark chocolate."

And guess what? More often than not, it seems like sugar is the leading ingredient, meaning that the dark chocolate isn't such a dark delight after all. The problem lies in the fact that there is no official classification for what percentage of cocoa a dark chocolate has to contain, and food manufactures seem more than happy to exploit this.

Fight Back: Whether you select a straight-up dark chocolate bar or a packaged food which claims to contain dark chocolate, be sure that chocolate liquor or cocoa mass, which is where the antioxidants can be found, is listed in the ingredient list before sugar. Ideally, you want a bar that says its cocoa content is at least 60 percent.

Packed with top-notch protein and a host of other essential nutrients, eggs are a near-perfect food for fitness fanatics. And even better if you can source free-range eggs; research shows they are even more awash in nutrients. Case in point: A 2014 study in the journal "Nutrition" discovered hens which were provided outdoor access made eggs with significantly higher vitamin D levels than the eggs produced by birds which were confined to the indoors. Exposure to sunlight is believed to be the reason why the hens were able to drop eggs that were richer in vitamin D.

But unscrambling egg labels can be tricky: "Free-range" eggs are supposed to come from hens allowed outdoor access while "free-run" means the birds are allowed to move freely in an indoor facility free of cages but likely don't spend anytime basking in sunshine. Unfortunately, neither label is tightly regulated. For example, the ease of outdoor access and the amount of time so-called "free-range" chickens actually spend in the sunshine is poorly regulated. And the range can mean anything from a large grassy field to a narrow pathway between barns to only a small concrete slab attached to a barn. What's more, there also isn't any mandate about how much time birds which produce "certified organic" eggs must spend in the great outdoors.

Fight Back: To be certain your white orbs come from birds that regularly see the light of day, it's best to befriend a local egg producer who raises smaller flocks and query them about their egg-producing methods. One tip off of a true free-range egg is a yolk that has an orange hue, which comes from the carotenoid antioxidants present in their foraged food.

Excessive salt intake may spike blood-pressure numbers, and some people find that it encourages water retention, leading to a physique that looks puffy, not chiselled. Logically, then, many fitness folks seek lower-sodium versions of their favorite foods.

"IF YOU'RE CONCERNED ABOUT YOUR SODIUM INTAKE, LOOK FOR THE LABEL "LOW SODIUM" ON ITEMS LIKE SOY SAUCE, FROZEN PIZZA, SOUPS, AND BREADS."

There's a big difference between "low sodium" and "reduced sodium," however. The latter simply means that it contains 25% less sodium than the original. If the original product such as chicken broth contained 900 milligrams of sodium per serving, the "reduced-sodium" version could still contain a lofty 675 milligrams of salt. Similarly, "light in sodium" entails the item only harbors 50 percent less sodium than its higher-salt counterpart.

Fight Back: If you're concerned about your sodium intake, look for the label "low sodium" on items like soy sauce, frozen pizza, soups, and breads. This is a guarantee that the product contains 140 milligrams of sodium or less per serving. "No salt added" means just that, no salt was added in the processing of the product. The nutrition facts panel may still show a certain amount of sodium, but this comes from sodium naturally present in the foods—such as tomatoes—used to make the product

http://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/what-advertisers-dont-want-you-to-know-about-food-labels.html?mcid=facenutrition03071714