Muscle Growth and Post-Workout Nutrition

In recent years, there has been huge interest in the topic of around workout nutrition for promoting optimal gains in strength and muscle size (prior to that, most interest had to to with recovery from exhaustive endurance exercise). And, as is so often the case, as research has developed, many ideas, some good and some bad, have developed out of that.

Early research into post-workout nutrition focused almost exclusively on endurance athletes and, really, the only issue of importance was refilling muscle glycogen and re-hydrating the athlete. For this reason the focus was on carbohydrates and fluids with little else considered. At some point, I recall it being the mid-90′s some early work suggested that adding protein to post-workout carbohydrates was beneficial in terms of glycogen re-synthesis and a new dietary trend started to form.

Now, it turns out to be a bit more complicated than that whether additional protein actually increases glycogen synthesis depends on a host of factors, primarily how much carbohydrate is provided. Simply, if sufficient carbohydrate is given following training, adding protein has no further benefit in terms of promoting glycogen re-synthesis.

In situations where insufficient carbs are consumed (by choice or otherwise), extra protein helps. Which isn’t to say that additional protein following training isn’t valuable for endurance athletes even if carbohydrate are sufficient but that’s not really the topic of today’s article.

While individuals involved in the strength sports and bodybuilding were quick to jump onto the post-workout carb/protein bandwagon, the research wasn’t really aimed at them. As well, there has always been a bit of a disconnect in using work on endurance athletes (who may be doing hours of exhaustive work) and trying to apply it to individuals in the weight room.

Differences in volume of training, fuel use and goals make using data on one group inappropriate for application to the others. It’s still common to see well-meaning nutritionists use the same guidelines for both strength/power athletes (including bodybuilders) and endurance athletes but that is simply silly.

In any case, work examining the impact of various combinations of post-workout nutrients in terms of promoting strength or hypertrophy would come later and, at this point, a huge amount of work has been done. I’m not going to get into every detail (the issue is discussed in absurd detail, 35 pages worth, in The Protein Book) of post-workout nutrition and will focus the article simply on the issue of protein, carbohydrates and the combination of the two in terms of how they impact on post-workout recovery and muscle growth.

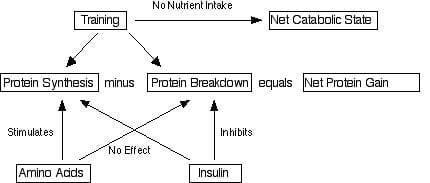

To understand what I’m going to say and why I think some current recommendations (especially the one saying that you only need protein post-workout) are not consistent with the research, I need to get into a few details regarding how training impacts on muscle growth and how nutrients impact on this. Don’t worry about the dense text, there’s a pretty graphic below to help explain it all. A pretty, pretty graphic.

.

How Does Muscle Grow?

Endlessly on the site, I’ve talked about how the primary stimulus for growth is progressive tension overload (with fatigue being a secondary factor) but, believe it or not, that’s not what I’m going to talk about here. Rather, I want to get a bit deeper into the processes of muscle growth. I’m not going to get full-blown molecular on you, just a bit more detail than I usually go into.

Now, the ultimate goal of getting bigger muscles is, well, getting bigger muscles. But what does that actually mean? Skeletal muscle is composed of a variety of different elements including protein (about 100-120 grams of actual protein per pound of muscle and yes I’m mixing grams and pounds), water (making up the majority), connective tissues, glycogen, minerals and a few other things. I’m going to focus on the actual protein component of it since that’s the bit that actually generates force, etc.

Protein in your muscle is no different than the protein found in dietary protein, it’s a long-chain of amino acids that have been attached to one another in the structure that makes up skeletal muscle (the various fibers and such). But how does this process work?

Simply, there are two competing processes that go into what ultimately happens to muscle mass which are protein synthesis and protein breakdown. Protein synthesis is simply the act of attaching amino acids into one another and making them into muscle. This is an energetically costly process and occurs through the actions of ribosomes (little cellular messengers that you learned about in 7th grade biology) acting under the instructions of mRNA (something else you forgot about from high school). So training turns on genes which get translated into mRNA which tell the ribosomes what to build and how to do it. That’s protein synthesis and you can think of it as ‘good’ when it comes to muscle growth.

The competing process is protein breakdown which is the opposite. Various specialty enzymes work against you, cleaving off amino acids from the already built skeletal muscle. This happens under the influence of hormones and other factors. Most tend to think of protein breakdown as ‘bad’ in the sense of muscle growth but it’s a touch more complicated than that. The ability to break down and rebuild tissues in the body (a process which is ongoing constantly, even when you’re ‘at rest’), provides the human body with a lot of adaptations flexibility. That is, it allows the body to adapt to changing demands and remodel itself based on the signal it gets from whatever is going on in your life. In that sense, protein breakdown is not ‘bad’.

Now, what happens to your muscle mass ultimately depends on the balance between these two competing processes. I’ve tried to illustrate this below with three possible scenarios.

Assuming your goal is bigger muscles, clearly 1 is the goal. But this also means that there are two primary ways that we can potentially impact on muscle growth. We can either increase protein synthesis, decrease protein breakdown or do both at the same time. And doing both at the same time would be expected to have the biggest impact.

There’s one more factoid you need to know which is this: heavy resistance training increases the rates of both protein synthesis AND breakdown. That is, training doesn’t just turn on one or another, it turns on both. This is probably a mechanism to help with the previously mentioned remodeling process. But both happen following training.

And with that background, now let’s look at how nutrients interact with all of this.

.

Protein, Carbohydrates or Both, Oh My!

While athletes are rarely that interested in technical details and only want the practical applications, to understand everything I want to talk about I need to look at a bit more detail, specifically how protein and carbohydrates interact with the processes of protein synthesis and breakdown discussed above. And it basically works out like this:

It’s actually a touch more complex than this. Protein can impact on protein breakdown under certain conditions and insulin can impact directly on protein synthesis (and there happens to be a big difference in terms of what happens at rest vs. after training). But for the most part, following training, the above will hold true.

Which leads us towards an ideal of post-workout nutrition. First and foremost I should point out that if you train and don’t eat anything afterwards (and this assumes you haven’t eaten a few hours before), the body will actually remain in a net catabolic state. That is, protein breakdown will be greater than protein synthesis. That’s bad. But only really applies if you’re training first thing in the morning after a fast (how many studies are done) and haven’t eaten anything.

But let’s assume that you eat something following training. Should it be protein, carbs, both, or some other combination? First let’s look at the single feeding studies. That is, let’s say that you could only choose one or the other following training, which should you choose. The answer there is clearly protein alone which will be vastly superior to carbohydrate alone. Because while consuming carbohydrates will decrease protein breakdown, only protein will increase protein synthesis (and provide the building blocks for building new muscle).

And this is also where a rather silly idea has come from in the post-workout recommendations. Folks will often state that “You only need protein post-workout because carbs don’t effect protein synthesis.” This is true but ignores the impact of decreasing protein breakdown on net protein gain.

Certainly increasing protein synthesis appears to be relatively more important than decreasing protein breakdown but the simple fact is that you get the biggest overall effect if you target both at the same time. Which means a combination of protein and carbohydrates.

I should probably mention dietary fat and the simple fact is that fat intake post-workout is woefully understudied. One study found no difference in anything with a meal containing fat vs one not-containing fat (so you folks insanely obsessed with not slowing gastric emptying by consuming dietary fat can stop worrying) but beyond that there’s little research. One study did find that full fat milk promoted protein synthesis better than skim milk following training but nobody is sure why. It wasn’t because more calories were consumed because the researchers also tested enough skim milk to match the calories of the whole milk; whole milk was still superior.

In any case, that’s the overall conclusion that I draw from looking at the body of literature: while protein alone is superior to carbohydrates alone, the combination of the two will have the greatest impact on promoting muscle growth (as well as having other beneficial effects on muscle glycogen, etc). How much of each? Well that depends on a host of other factors that will have to wait for a later article (or see The Protein Book).

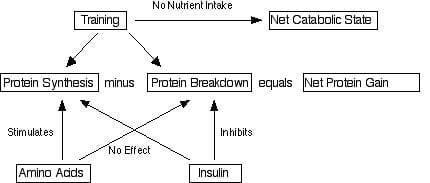

I’ve shown this schematically in the graphic below, showing how both training and nutrients impact on the processes discussed above.

Arrows are neat!

Arrows are neat!

So that’s that: protein is better than carbohydrate following training but protein plus carbohydrates is optimal. Good luck with your muscles.

In recent years, there has been huge interest in the topic of around workout nutrition for promoting optimal gains in strength and muscle size (prior to that, most interest had to to with recovery from exhaustive endurance exercise). And, as is so often the case, as research has developed, many ideas, some good and some bad, have developed out of that.

Early research into post-workout nutrition focused almost exclusively on endurance athletes and, really, the only issue of importance was refilling muscle glycogen and re-hydrating the athlete. For this reason the focus was on carbohydrates and fluids with little else considered. At some point, I recall it being the mid-90′s some early work suggested that adding protein to post-workout carbohydrates was beneficial in terms of glycogen re-synthesis and a new dietary trend started to form.

Now, it turns out to be a bit more complicated than that whether additional protein actually increases glycogen synthesis depends on a host of factors, primarily how much carbohydrate is provided. Simply, if sufficient carbohydrate is given following training, adding protein has no further benefit in terms of promoting glycogen re-synthesis.

In situations where insufficient carbs are consumed (by choice or otherwise), extra protein helps. Which isn’t to say that additional protein following training isn’t valuable for endurance athletes even if carbohydrate are sufficient but that’s not really the topic of today’s article.

While individuals involved in the strength sports and bodybuilding were quick to jump onto the post-workout carb/protein bandwagon, the research wasn’t really aimed at them. As well, there has always been a bit of a disconnect in using work on endurance athletes (who may be doing hours of exhaustive work) and trying to apply it to individuals in the weight room.

Differences in volume of training, fuel use and goals make using data on one group inappropriate for application to the others. It’s still common to see well-meaning nutritionists use the same guidelines for both strength/power athletes (including bodybuilders) and endurance athletes but that is simply silly.

In any case, work examining the impact of various combinations of post-workout nutrients in terms of promoting strength or hypertrophy would come later and, at this point, a huge amount of work has been done. I’m not going to get into every detail (the issue is discussed in absurd detail, 35 pages worth, in The Protein Book) of post-workout nutrition and will focus the article simply on the issue of protein, carbohydrates and the combination of the two in terms of how they impact on post-workout recovery and muscle growth.

To understand what I’m going to say and why I think some current recommendations (especially the one saying that you only need protein post-workout) are not consistent with the research, I need to get into a few details regarding how training impacts on muscle growth and how nutrients impact on this. Don’t worry about the dense text, there’s a pretty graphic below to help explain it all. A pretty, pretty graphic.

.

How Does Muscle Grow?

Endlessly on the site, I’ve talked about how the primary stimulus for growth is progressive tension overload (with fatigue being a secondary factor) but, believe it or not, that’s not what I’m going to talk about here. Rather, I want to get a bit deeper into the processes of muscle growth. I’m not going to get full-blown molecular on you, just a bit more detail than I usually go into.

Now, the ultimate goal of getting bigger muscles is, well, getting bigger muscles. But what does that actually mean? Skeletal muscle is composed of a variety of different elements including protein (about 100-120 grams of actual protein per pound of muscle and yes I’m mixing grams and pounds), water (making up the majority), connective tissues, glycogen, minerals and a few other things. I’m going to focus on the actual protein component of it since that’s the bit that actually generates force, etc.

Protein in your muscle is no different than the protein found in dietary protein, it’s a long-chain of amino acids that have been attached to one another in the structure that makes up skeletal muscle (the various fibers and such). But how does this process work?

Simply, there are two competing processes that go into what ultimately happens to muscle mass which are protein synthesis and protein breakdown. Protein synthesis is simply the act of attaching amino acids into one another and making them into muscle. This is an energetically costly process and occurs through the actions of ribosomes (little cellular messengers that you learned about in 7th grade biology) acting under the instructions of mRNA (something else you forgot about from high school). So training turns on genes which get translated into mRNA which tell the ribosomes what to build and how to do it. That’s protein synthesis and you can think of it as ‘good’ when it comes to muscle growth.

The competing process is protein breakdown which is the opposite. Various specialty enzymes work against you, cleaving off amino acids from the already built skeletal muscle. This happens under the influence of hormones and other factors. Most tend to think of protein breakdown as ‘bad’ in the sense of muscle growth but it’s a touch more complicated than that. The ability to break down and rebuild tissues in the body (a process which is ongoing constantly, even when you’re ‘at rest’), provides the human body with a lot of adaptations flexibility. That is, it allows the body to adapt to changing demands and remodel itself based on the signal it gets from whatever is going on in your life. In that sense, protein breakdown is not ‘bad’.

Now, what happens to your muscle mass ultimately depends on the balance between these two competing processes. I’ve tried to illustrate this below with three possible scenarios.

- Protein synthesis > Protein breakdown = Muscle mass increases

- Protein synthesis = Protein breakdown = No change in muscle mass

- Protein synthesis < Protein breakdown = Muscle mass decreases

Assuming your goal is bigger muscles, clearly 1 is the goal. But this also means that there are two primary ways that we can potentially impact on muscle growth. We can either increase protein synthesis, decrease protein breakdown or do both at the same time. And doing both at the same time would be expected to have the biggest impact.

There’s one more factoid you need to know which is this: heavy resistance training increases the rates of both protein synthesis AND breakdown. That is, training doesn’t just turn on one or another, it turns on both. This is probably a mechanism to help with the previously mentioned remodeling process. But both happen following training.

And with that background, now let’s look at how nutrients interact with all of this.

.

Protein, Carbohydrates or Both, Oh My!

While athletes are rarely that interested in technical details and only want the practical applications, to understand everything I want to talk about I need to look at a bit more detail, specifically how protein and carbohydrates interact with the processes of protein synthesis and breakdown discussed above. And it basically works out like this:

- Protein (amino acids) stimulate protein synthesis but have no impact on protein breakdown.

- Insulin (secondary to carb consumption) inhibits protein breakdown with no impact on protein synthesis.

It’s actually a touch more complex than this. Protein can impact on protein breakdown under certain conditions and insulin can impact directly on protein synthesis (and there happens to be a big difference in terms of what happens at rest vs. after training). But for the most part, following training, the above will hold true.

Which leads us towards an ideal of post-workout nutrition. First and foremost I should point out that if you train and don’t eat anything afterwards (and this assumes you haven’t eaten a few hours before), the body will actually remain in a net catabolic state. That is, protein breakdown will be greater than protein synthesis. That’s bad. But only really applies if you’re training first thing in the morning after a fast (how many studies are done) and haven’t eaten anything.

But let’s assume that you eat something following training. Should it be protein, carbs, both, or some other combination? First let’s look at the single feeding studies. That is, let’s say that you could only choose one or the other following training, which should you choose. The answer there is clearly protein alone which will be vastly superior to carbohydrate alone. Because while consuming carbohydrates will decrease protein breakdown, only protein will increase protein synthesis (and provide the building blocks for building new muscle).

And this is also where a rather silly idea has come from in the post-workout recommendations. Folks will often state that “You only need protein post-workout because carbs don’t effect protein synthesis.” This is true but ignores the impact of decreasing protein breakdown on net protein gain.

Certainly increasing protein synthesis appears to be relatively more important than decreasing protein breakdown but the simple fact is that you get the biggest overall effect if you target both at the same time. Which means a combination of protein and carbohydrates.

I should probably mention dietary fat and the simple fact is that fat intake post-workout is woefully understudied. One study found no difference in anything with a meal containing fat vs one not-containing fat (so you folks insanely obsessed with not slowing gastric emptying by consuming dietary fat can stop worrying) but beyond that there’s little research. One study did find that full fat milk promoted protein synthesis better than skim milk following training but nobody is sure why. It wasn’t because more calories were consumed because the researchers also tested enough skim milk to match the calories of the whole milk; whole milk was still superior.

In any case, that’s the overall conclusion that I draw from looking at the body of literature: while protein alone is superior to carbohydrates alone, the combination of the two will have the greatest impact on promoting muscle growth (as well as having other beneficial effects on muscle glycogen, etc). How much of each? Well that depends on a host of other factors that will have to wait for a later article (or see The Protein Book).

I’ve shown this schematically in the graphic below, showing how both training and nutrients impact on the processes discussed above.

Arrows are neat!

Arrows are neat!So that’s that: protein is better than carbohydrate following training but protein plus carbohydrates is optimal. Good luck with your muscles.

Comment