By David Dellanave

You wake up in the morning, stretch, and roll out of bed. After brushing your teeth with one hand and checking email on your phone with the other, you walk downstairs to make coffee and breakfast.

After eating, you hop in the car to drive to the gym. As you’re hurtling down the freeway at a speed six times faster than a human can travel under their own power, you make almost imperceptible adjustments to the steering wheel to avoid playing bumper cars with drivers who didn’t check their email when they first woke up.

It’s arm day, so you easily grab a dumbbell that weighs more than what some people deadlift and sit down for your first set of concentration curls. You focus all of your mental energy on feeling your biceps contract as you curl the weight up.

Hold on.

By the time you pulled into your parking spot at the gym, you will have, without a thought, performed at least a dozen tasks that are currently impossible for any single piece of technology to do alone.

Scientists and engineers have been trying in vain to duplicate what the body has done with grace and ease for hundreds of years. Something as simple and unremarkable to us as walking is currently impossible for a man-made robot to do smoothly. Humans need only to decide on an outcome and the body figures out how to coordinate the muscles and movements to accomplish it. Complex sports like football, rugby, or MMA wouldn’t exist if the athletes had to think about every muscle movement involved in a cut, takedown, or tackle.

Yet, surprisingly, some people attempt to override and exert control over this high-tech piece of machinery. Trying to overthink how you’re moving when you’re training is subtracting pounds from workout, and it’s costing you muscle.

The Mind-Muscle Connection

Much has been written about the mind-muscle connection, with many trainers and trainees encouraging a focus on how a movement feels in your mind while you’re doing it. The idea is that you can create a greater mental link to your musculature by intently focusing on the muscles that are moving. The premise is that if you have a superior map of the muscle, it will grow more and in a more complete way. I’m here to tell you to toss that idea.

The technical term for the “mind-muscle connection” is an internal focus, and has been studied extensively. Coaches have wanted to know for decades if it’s better to focus on how a movement feels or the outcome of the desired movement. Focusing on the outcome means simply moving from Point A to Point B, or using something outside of the body as a reference such as “reach for the ceiling.” The results are absolutely conclusive: External focus is superior in every situation.

Very rarely does research appear to be as decisive as what we currently know about external focus. It seems that whatever metric you want to improve: speed, accuracy, power, or total work output, external focus gets you more of it. There is a related phenomenon worth being aware of, because it has obviously confused people. Studies on internal focus have shown greater EMG activity in both the target muscle area and all around it. When the studies have measured both EMG and actual muscular output, however, there is no change in output despite greater EMG. The explanation is obvious: Focusing on how to move confuses your nervous system, which already knows how to move, leading to stray muscle activation noise. Muscle activation on its own doesn’t lead to hypertrophy.

Think of it as walking into a room of highly competent people, known for their ability to self-organize and delegate tasks to the most qualified individuals. You have two options. You could shout instructions into the room, telling each person what their exact instructions are at the same time and hope everyone catches the right message, and hope that the way you’ve decided to distribute the task is the most effective way to get the job done. Alternatively, you could write down the desired outcome and let them sort out the best way to distribute the work and complete the task.

So you can try to run the show if you want to, but there is a cost, and the cost is that you’re going to get less work done. It’s not that focusing internally doesn’t work, period — it’s that focusing externally worksbetter. So why have so many exceptional bodybuilders sworn by the mind-muscle connection for so long?

The Confounding Factor

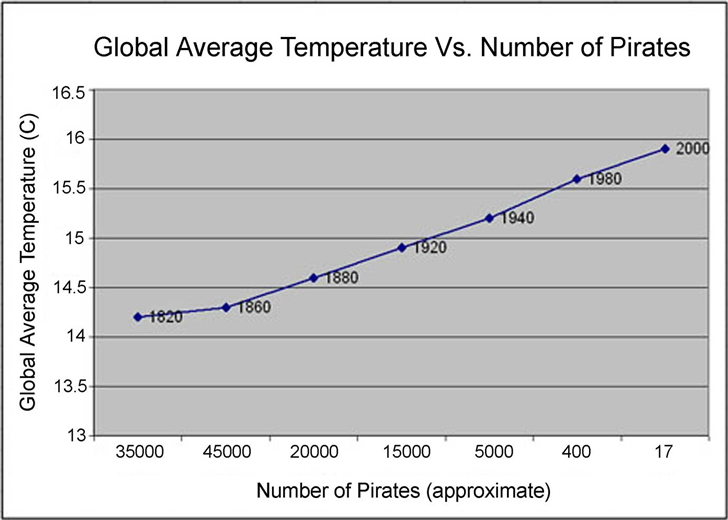

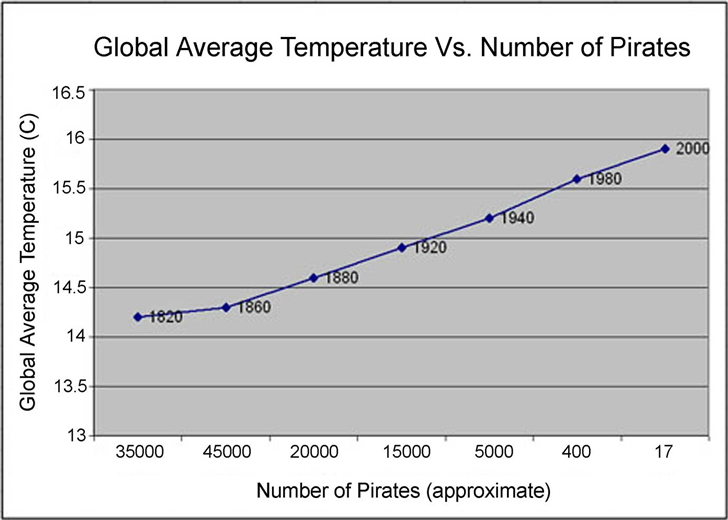

In statistics, the confounding factor is the variable that affects the apparent outcome of an experiment. If the variable isn’t controlled for, the conclusion drawn from the experiment can be completely wrong and you could believe that the decline of pirates is the cause of global warming.

I believe the single greatest advantage that bodybuilders believe is conferred from focusing on the feeling of a movement is that of training slightly varied ranges of motion by making small changes to exercises.

We know from an important study by led Jose Antonio, Ph.D., that muscles can be innervated differently based on the joint angles involved in the movement. Varying exercise selection and distributing more total work over the muscle has a proven effect on muscle growth. No matter how hard you think about how the flex feels, lifting 30 percent of your one-rep max is not going to recruit the same amount of muscle fibers as lifting 90 percent of your max.

Change the exercise, or change a part of the exercise, and you change the muscle tissue involved.

Cover all the possible ranges of motion of the tissue, and grow everywhere.

What About Technique?

Technique matters. How exactly you perform a movement can drastically alter muscle recruitment in the body. Both external “push the floor away” and internal “squeeze the glutes” cues can be used to alter technique. There may be cases in which internal cues seem to work better when the intended targets of an exercise aren’t moving due to a dysfunction. Due to limitations in research done using EMG, there exists no definitive evidence that internal cueing actually facilitates desired muscle recruitment or that it’s better than an external focus, even in such cases. Should you use internal cues to reinforce technique, use only the minimal effective amount to restore the movement. Once the parts are moving, stop thinking about it and just move.

How Does Muscle Grow?

Brad Schoenfeld, M.Sc., CSCS, wrote the current definitive piece of literature on the mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy. Many of his conclusions, which cut through the fog of confusion and contradictory research findings, are useful in understanding what matters most in training for maximum muscle hypertrophy. He synopsizes that muscles hypertrophy when there is a combination of mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress.

At the risk of over-simplifying all the variables Schoenfeld examined, it’s not inaccurate to say that more work at the highest possible power output, recruiting the most possible muscle fibers, and using varying intensities is the ticket to gainsville.

Increasing muscle activation alone — which can only be approximated via EMG — is not enough to create muscle hypertrophy without the other variables. If it were, we’d all rock those electronic belts that shock your abs into a six pack.

Put It Together, Grow More

Focusing internally on movement carries the added cost of increasing EMG without increasing the output or work done. Directing attention to the outcome — and only the outcome — decreases spurious muscle activation and allows more work to be done resulting in more mechanical tension, more muscle damage, and more metabolic stress. That’s a muscle hypertrophy cocktail.

To develop the muscle fully we know both from bodybuilder tradition and scientific study that changing the range of motion of an exercise via the joint angles changes the path of development along the muscle. If you want to develop the inside of the biceps, you have to turn your palm up, not just think about how it feels.

The path to ultimate muscle gains is to stop trying to feel a movement, have a laser focus on simply moving the weight, and use as many ranges of motion as you possibly can in your training. You’ve got the technology — just use it to get work done.

Bron

You wake up in the morning, stretch, and roll out of bed. After brushing your teeth with one hand and checking email on your phone with the other, you walk downstairs to make coffee and breakfast.

After eating, you hop in the car to drive to the gym. As you’re hurtling down the freeway at a speed six times faster than a human can travel under their own power, you make almost imperceptible adjustments to the steering wheel to avoid playing bumper cars with drivers who didn’t check their email when they first woke up.

It’s arm day, so you easily grab a dumbbell that weighs more than what some people deadlift and sit down for your first set of concentration curls. You focus all of your mental energy on feeling your biceps contract as you curl the weight up.

Hold on.

By the time you pulled into your parking spot at the gym, you will have, without a thought, performed at least a dozen tasks that are currently impossible for any single piece of technology to do alone.

Scientists and engineers have been trying in vain to duplicate what the body has done with grace and ease for hundreds of years. Something as simple and unremarkable to us as walking is currently impossible for a man-made robot to do smoothly. Humans need only to decide on an outcome and the body figures out how to coordinate the muscles and movements to accomplish it. Complex sports like football, rugby, or MMA wouldn’t exist if the athletes had to think about every muscle movement involved in a cut, takedown, or tackle.

Yet, surprisingly, some people attempt to override and exert control over this high-tech piece of machinery. Trying to overthink how you’re moving when you’re training is subtracting pounds from workout, and it’s costing you muscle.

The Mind-Muscle Connection

Much has been written about the mind-muscle connection, with many trainers and trainees encouraging a focus on how a movement feels in your mind while you’re doing it. The idea is that you can create a greater mental link to your musculature by intently focusing on the muscles that are moving. The premise is that if you have a superior map of the muscle, it will grow more and in a more complete way. I’m here to tell you to toss that idea.

The technical term for the “mind-muscle connection” is an internal focus, and has been studied extensively. Coaches have wanted to know for decades if it’s better to focus on how a movement feels or the outcome of the desired movement. Focusing on the outcome means simply moving from Point A to Point B, or using something outside of the body as a reference such as “reach for the ceiling.” The results are absolutely conclusive: External focus is superior in every situation.

Very rarely does research appear to be as decisive as what we currently know about external focus. It seems that whatever metric you want to improve: speed, accuracy, power, or total work output, external focus gets you more of it. There is a related phenomenon worth being aware of, because it has obviously confused people. Studies on internal focus have shown greater EMG activity in both the target muscle area and all around it. When the studies have measured both EMG and actual muscular output, however, there is no change in output despite greater EMG. The explanation is obvious: Focusing on how to move confuses your nervous system, which already knows how to move, leading to stray muscle activation noise. Muscle activation on its own doesn’t lead to hypertrophy.

Think of it as walking into a room of highly competent people, known for their ability to self-organize and delegate tasks to the most qualified individuals. You have two options. You could shout instructions into the room, telling each person what their exact instructions are at the same time and hope everyone catches the right message, and hope that the way you’ve decided to distribute the task is the most effective way to get the job done. Alternatively, you could write down the desired outcome and let them sort out the best way to distribute the work and complete the task.

So you can try to run the show if you want to, but there is a cost, and the cost is that you’re going to get less work done. It’s not that focusing internally doesn’t work, period — it’s that focusing externally worksbetter. So why have so many exceptional bodybuilders sworn by the mind-muscle connection for so long?

The Confounding Factor

In statistics, the confounding factor is the variable that affects the apparent outcome of an experiment. If the variable isn’t controlled for, the conclusion drawn from the experiment can be completely wrong and you could believe that the decline of pirates is the cause of global warming.

I believe the single greatest advantage that bodybuilders believe is conferred from focusing on the feeling of a movement is that of training slightly varied ranges of motion by making small changes to exercises.

We know from an important study by led Jose Antonio, Ph.D., that muscles can be innervated differently based on the joint angles involved in the movement. Varying exercise selection and distributing more total work over the muscle has a proven effect on muscle growth. No matter how hard you think about how the flex feels, lifting 30 percent of your one-rep max is not going to recruit the same amount of muscle fibers as lifting 90 percent of your max.

Change the exercise, or change a part of the exercise, and you change the muscle tissue involved.

Cover all the possible ranges of motion of the tissue, and grow everywhere.

What About Technique?

Technique matters. How exactly you perform a movement can drastically alter muscle recruitment in the body. Both external “push the floor away” and internal “squeeze the glutes” cues can be used to alter technique. There may be cases in which internal cues seem to work better when the intended targets of an exercise aren’t moving due to a dysfunction. Due to limitations in research done using EMG, there exists no definitive evidence that internal cueing actually facilitates desired muscle recruitment or that it’s better than an external focus, even in such cases. Should you use internal cues to reinforce technique, use only the minimal effective amount to restore the movement. Once the parts are moving, stop thinking about it and just move.

How Does Muscle Grow?

Brad Schoenfeld, M.Sc., CSCS, wrote the current definitive piece of literature on the mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy. Many of his conclusions, which cut through the fog of confusion and contradictory research findings, are useful in understanding what matters most in training for maximum muscle hypertrophy. He synopsizes that muscles hypertrophy when there is a combination of mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress.

At the risk of over-simplifying all the variables Schoenfeld examined, it’s not inaccurate to say that more work at the highest possible power output, recruiting the most possible muscle fibers, and using varying intensities is the ticket to gainsville.

Increasing muscle activation alone — which can only be approximated via EMG — is not enough to create muscle hypertrophy without the other variables. If it were, we’d all rock those electronic belts that shock your abs into a six pack.

Put It Together, Grow More

Focusing internally on movement carries the added cost of increasing EMG without increasing the output or work done. Directing attention to the outcome — and only the outcome — decreases spurious muscle activation and allows more work to be done resulting in more mechanical tension, more muscle damage, and more metabolic stress. That’s a muscle hypertrophy cocktail.

To develop the muscle fully we know both from bodybuilder tradition and scientific study that changing the range of motion of an exercise via the joint angles changes the path of development along the muscle. If you want to develop the inside of the biceps, you have to turn your palm up, not just think about how it feels.

The path to ultimate muscle gains is to stop trying to feel a movement, have a laser focus on simply moving the weight, and use as many ranges of motion as you possibly can in your training. You’ve got the technology — just use it to get work done.

Bron